Unit 3: Organizing the Field

Key Branches and Orientations within Cultural Mapping

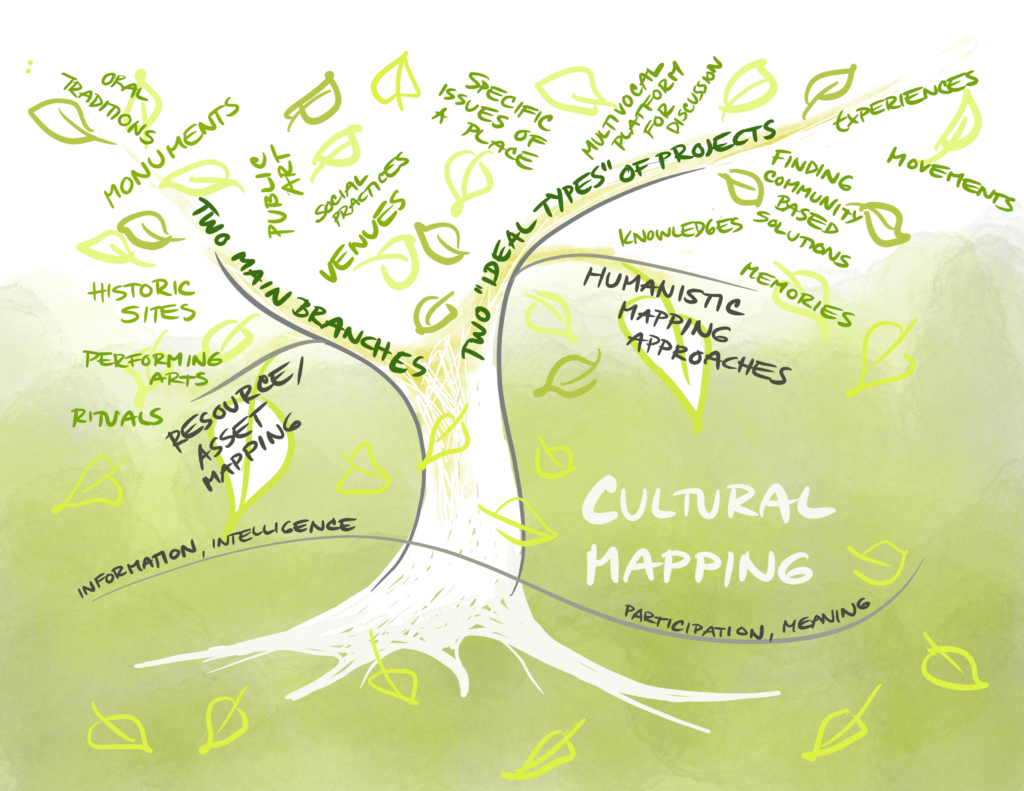

Two Main Branches

For most people engaged in cultural mapping, their focus understandably tends to be on the task at hand, without extensive self-reflection on the place of the mapping in the larger field of practice. Social activists, for example, are intent on challenging received systems of authority and power; policy-makers focus their attention on identifying and nurturing creative industries and development; cultural planners seek ways to make local culture more visible and engage communities in participatory decision-making; artists emphasize the aesthetic and seek to provide new perspectives, new ways of seeing; academics bring a research lens and

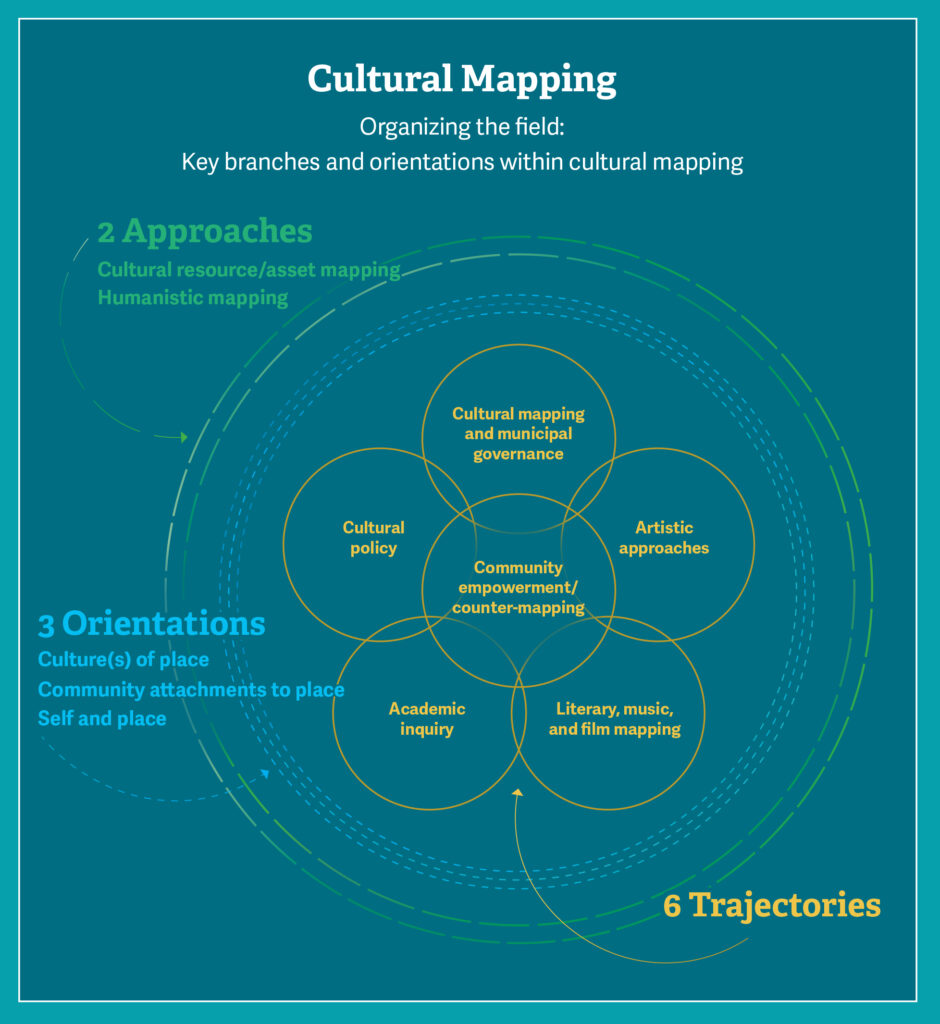

methodological rigour to refine cartographic practices generally; and people from all walks of life are motivated to locate their interest in art objects and art-making as ‘mappable’ pursuits. Given the diversity of motives and approaches, it is helpful to provide a bird’s eye view of the field. Here, we present you with two organizing schemas. First, we note that cultural mapping has been evolving along two main branches, corresponding to “ideal types”: (1) cultural resource/asset mapping and (2) ‘humanistic’ mapping approaches. Second, we point to three general orientations within cultural mapping, organized by each project’s main thematic focal point.

Two “ideal types”

As the number of cultural mapping projects has grown and they have become more visible, two “ideal types” of projects have become evident: cultural resource/asset mapping and ‘humanistic’ mapping approaches. This general organization has influenced the way the field sees and defines itself, as well as the ways in which efforts are applied to advance methodological practices in each of these areas.

Cultural resource/asset mapping

This first branch begins with cultural assets. It seeks to identify and document tangible and intangible assets of a place, with the aim of developing and incorporating culture and creative industries in strategies that address broader issues of a locale. In this context, a general distinction has often been made between asset mapping and identity mapping. This division typically distinguishes between physical or tangible cultural assets, such as cultural venues, public art works, historic sites, monuments, and identifiable organizations and persons; and intangible elements that provide a sense of place and identity for a locale, which can incorporate both historical and contemporary aspects. As examples, UNESCO defines intangible cultural heritage as including “oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts” (see https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-isintangible-heritage-00003). Contemporary intangible cultural aspects can also include artistic and craft skills and expressions specific to a place, and informal social arrangements that enable cultural/artistic knowledge and know-how to be shared. Over time, tangible and intangible dimensions have become increasingly intertwined and are, more and more, considered together.

‘Humanistic’ mapping approaches

The second branch, associated with the rise of critical cartography (Dodge, Kitchen, and Perkins, 2009), begins with a culturally sensitive, humanistic approach to understanding specific issues of a place, creating a multivocal platform for discussion and finding community-based solutions. The focus is centred on the people who are resident, living, and interacting within a territory, and it is their knowledges, experiences, movements, and memories that become integral to defining the cultural assets and meanings of the territory. The topics being examined, discussed, and mapped can include both tangible and intangible elements. Artistic approaches within this branch can help to articulate the felt sense of place that traditional mapping approaches often miss. Artists can also help foreground the aesthetic dimensions of a community’s self-expression and identity.

While the former (first branch) approach tends to emphasize the documentation of “information” and the development of “creative sector intelligence,” the latter tends to focuses more on “participation” and “meaning.” However, they are not mutually exclusive and are increasingly blended and mutually informing approaches. Taken together, the two areas of cultural mapping seek to combine the tools of modern cartography with vernacular and participatory methods of storytelling to represent spatially, visually, and textually the authentic knowledge, assets, values, views, and memories of local communities.

Three orientations

We can observe three general orientations within cultural mapping, characterized by the main focal point of a project rather than the nature of the types of items that are mapped. These orientations combine the motive and purpose of each mapping project, and can be categorized as follows:

- Self and place

- Community attachments to place

- Culture(s) of place

These orientations may incorporate methodologies and practices from both the cultural resource/asset mapping approach and the humanistic approach described above.

Self and Place

In these projects, the mapper focuses on personal attachments and connections between an individual and a place. The “self” may be themselves or another person. The mapping includes recording not only travel routes but may also explore personal feelings, impressions, memories, and other place-specific narratives and connections. While the focus is on individual stories and experiences, the compilation of multiple individual maps can create a collective sense of a place. Furthermore, informed by journey mapping approaches in health care and business, cultural mapping practices have been applied to other social issues.

For example, two projects led by local art galleries and working with universities, give voice to individual experiences and a highly personal sense of place.

Community and Place

Projects in this category focus on relations between a collective of people and the territory they inhabit, and on how places are meaningful to the communities

that live there. They aim to characterize the connection between culture, territory, and the people who live there. The knowledge collected can be collective in nature (that is, without enabling individualized extractions) or can be a pluralistic compilation of individual voices to provide collective messages and impressions, highlighting shared commonalities and differences. They can articulate the face(s) of a community.

Culture(s) of Place

These projects attend to the cultural dimensions and aspects particular to a locale that make it distinct or significant.

| Unit 3 Activities Check your understanding of Unit 3 by completing the quick, automatically assessed activities below. The more complex reflective journal practice will look at your project from Unit 1 through a lens of the two main branches and three orientations. You are invited to: |

References:

Dodge, M., R. Kitchin, and C. Perkins. (2009). Rethinking Maps: New Frontiers in Cartographic Theory. London: Routledge.

Stevenson, J., & Harrington, S. (Eds.). (2005). Islands in the Salish Sea: A community atlas. TouchWood Editions.

Banis, D., & Shobe, H. (2015). Portlandness: a cultural atlas.